The front and back of a prosthetic eye (conformer). These must be continually replaced with larger prostheses as the patient’s eye sockets grow. (Source: Hans G at German Language Wikipedia)

Thanks to Harry Potter and horn-rimmed hipsters, eyeglass wearers have never been more ubiquitous—or profitable. With a whopping $35 billion in retail sales, the U.S. vision care market is only growing;1 it’s no wonder, considering that 30% of the U.S. population is nearsighted,2 while an additional 10% of the population is farsighted.3 Most people can relate to the everyday annoyances of grimy glasses and dropped contacts; but far fewer have even heard of anophthalmia, an extremely rare condition in which one or both eyes completely fail to form.

Occurring in an estimated 1:30,000 births,4 anophthalmia can arise from both genetic and environmental causes, including early gestational exposure to infections or x-rays.5 For children born without eyes (or sometimes even small eyes, as in microphthalmia), blindness is permanent; the only available treatment is purely cosmetic. From the very beginning, newborns are fitted for prosthetic eyes, so as to encourage proper eye socket growth. These prosthetic structures, called conformers, are continually replaced, as the baby grows. Indeed, a baby’s first few conformers appear black in the eye socket; conformers get changed so often, that they aren’t painted to look realistic, until the child is 2 years old.6

Several genes have already been linked to anophthalmia and microphthalmia, but most details of pathogenesis remain unclear. In fact, the major genetic cause, mutations in Sox2, only accounts for 10-20% of disease cases.7 However, new evidence has just implicated another gene, MAB21L2.

MAB21L2 recently gained popularity on BioGPS, coinciding with a new publication demonstrating a link between MAB21L2 mutations and severe eye defects.

Originally identified in C.elegans, MAB21L2 (Male Abnormal 21 gene family) is named for its role in the development of sensory rays, a male-specific organ involved in mating.8 In vertebrates, its function is less well understood, though MAB21L2 has long since been associated with multiple developmental events, including eye formation. Indeed, mutations in MAB21L2 cause severe eye malformation—and eventually mid-gestational death—in mice.9 In humans, MAB21L2 mutations have only recently been discovered in patients with anophthalmia and microphthalmia.10 Multiple mechanisms have been proposed to explain MAB21L2’s effect on eye development, but none have been proven yet, and research is ongoing.

There are still a frightening number of ways that anophthalmia can occur, but investigating the link between MAB21L2 and eye malformation might help us to better understand—and certainly, appreciate—normal eye development. So the next time your glasses fog up, or contacts fall out, ignore those little inconveniences—just remember to be grateful for your eyes, and the intricate (though, perhaps delicate) cellular processes that create them.

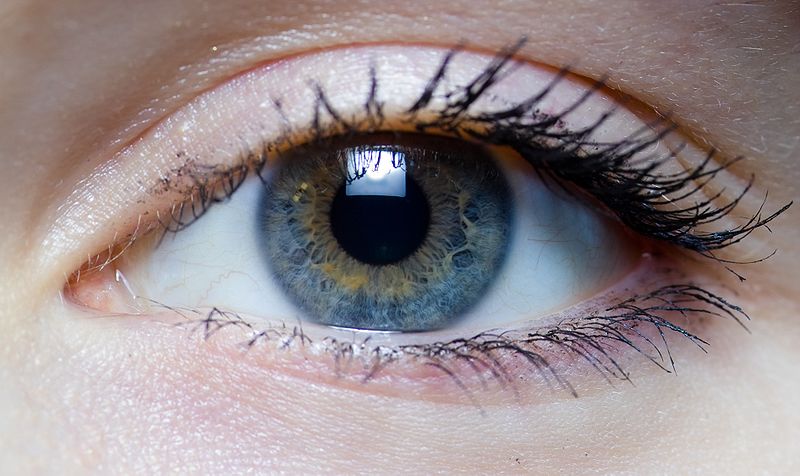

Thank you, eyes. (Source: Laitr Keiows at Wikimedia Commons)

References:

- “Retail sales of the vision care market in the United States from 2011 to 2013, by sector (in million U.S. dollars)” Statista: The Statistics Portal. Retrieved 8 August 2014 from http://www.statista.com/statistics/256257/retail-sales-of-the-vision-care-market-in-the-us-by-sector/ [↩]

- “Myopia” National Eye Institute. Retrieved 8 August 2014 from http://www.nei.nih.gov/eyedata/myopia.asp [↩]

- “Hyperopia” National Eye Institute. Retrieved 8 August 2014 from http://www.nei.nih.gov/eyedata/hyperopia.asp [↩]

- Williamson KA, Fitzpatrick DR. (2014) The genetic architecture of microphthalmia, anophthalmia and coloboma. Eur J Med Genet S1769-7212(14)00114-1. [↩]

- Verma AS and FitzPatrick DR. (2007) Anophthalmia and microphthalmia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2:47. [↩]

- “Facts about anophthalmia and microphthalmia” National Eye Institute. Retrieved 8 August 2014 from http://www.nei.nih.gov/health/anoph/anophthalmia.asp#3 [↩]

- Verma AS and FitzPatrick DR. (2007) Anophthalmia and microphthalmia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2:47. [↩]

- Baldessari et al. (2004) MAB21L2, a vertebrate member of the Male-abnormal 21 family, modulates BMP signaling and interacts with SMAD1. BMC Cell Biol 5(1):48. [↩]

- Yamada R et al. (2004) Requirement for Mab21l2 during development of murine retina and ventral body wall. Dev Biol 274(2):295-307. [↩]

- Rainger J et al. (2014) Monoallelic and biallelic mutations in MAB21L2 cause a spectrum of major eye malformations. Am J Hum Gene 94(6):915-23. [↩]